Navigating Identity: A Pride Month Conversation with Alyy Patel, Author and South Asian Queer Advocate

/Content warning: This blog post discusses mental health challenges and alludes to suicidal ideation. If it's the right time for you, we invite you to read and engage with this story.

Pride Month is a time for the LGBTQ+ community and its allies to come together, celebrate queerness in all its forms, and build toward a more inclusive, empathetic, and compassionate future.

Alyy Patel — queer LGBTQ+ activist, scholar, speaker, and FriesenPress author — lives those values year-round. At age 22, Alyy founded the Queer South Asian Women’s Network — a Canadian nonprofit aimed at bringing this underrepresented community together. Currently working on her PhD at the University of British Columbia, Alyy has made numerous contributions to Canadian research on Queer South Asian Women’s issues in the diaspora.

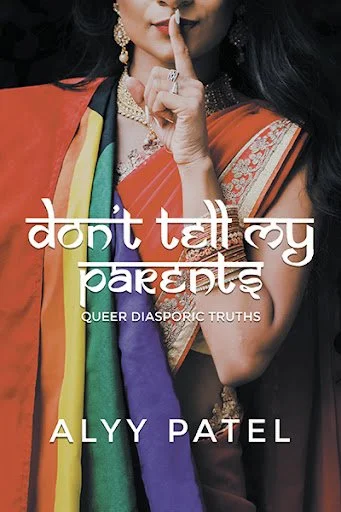

But despite these many accomplishments, Alyy’s proudest achievement is their debut book, Don’t Tell My Parents, published with FriesenPress. Don’t Tell My Parents is a fearless and, at times, raw exploration of Alyy’s journey of self-discovery, healing, and the intersectional experiences that shape their identity.

We spoke with Alyy to learn more about how writing poetry became a transformative outlet for processing pain. We discovered how their book challenges prevailing narratives surrounding closeted individuals in queer communities, and sheds light on the complex experience of being a South Asian queer person, often overlooked or misunderstood.

Alyy’s exploration of identity, healing, and self-acceptance offers a relevant and invaluable perspective that amplifies the voices of marginalized communities — not only during Pride, but during all months of the year.

Here is our conversation:

Let’s start at the beginning: where did Don’t Tell My Parents begin?

Writing this book was truly about getting a sense of justice for myself, to not be suffering in silence any longer. Displaying my truths out there in a book, in a poetic form, that took me from point A to points B, C, and D, and then finally allowed me to come into myself.

I didn’t intend to write a book. I was writing poetry literally on the Notes app of my phone for about two years to track my own thought process while I was in abusive relationships. I didn’t really realize at the time that they were abusive — writing poems felt like a way of keeping track of my thoughts and feelings about what I was going through. Writing was a self-growth experience.

There’s a section of the book that is also about not being supported or accepted [as queer] by my family. I can’t speak as openly as I would like about those experiences of toxicity in relationships and family. I can’t say, “this happened to me, and this person did this,” so I’m going to express myself poetically so I can feel some sense of justice to myself.

Was there a light-bulb moment when you realized you wanted to publish these poems as a book?

Before this book, I had never posted my poetry anywhere. I was very shy and, at that point, I wasn’t a very creative person either. I was worried about what people would say — that kind of rhetoric really creeped up on me. But that light-bulb moment for me was actually midway through writing [what would become] the book.

I was talking to a friend who told me that she writes poetry, and so I told her, “Oh, you know what? I do too.” That was the first time I shared [anything I had written]. I copy and pasted all my poems from my notes, put it in a Google Doc, and I sent it over. But as I was looking at it, I realized, “Oh, this actually kind of reads in a really interesting way. It looks like it could be a book.” I started entertaining the idea of publishing it. I’d always wanted to write a book, but I didn’t think I would actually move forward with it.

I kind of left it at that thought, but I kept building on the poems. One more toxic relationship later, I hit a breaking point [thinking], “I've had enough, and I’m not dealing with this anymore. And I will be putting my truths out there because I need to liberate myself from all of this darkness that I’m holding onto.” It was really one of those impulsive moments of, I need to liberate myself. This needs to happen. I am going to have a break.

Can you speak about the impact that writing and poetry had on helping you process some of the difficult things you had gone through?

The entire book really represents my healing process, and my journey to self-acceptance.

In one part, it is my journey of healing the South Asian cultural scripts that I picked up from childhood of not putting yourself first as a South Asian daughter. Putting everybody else before you, especially your lovers. Putting even just the narrative of family and choosing basically anybody over yourself first, which is what led me into those abusive relationships.

In another way, it’s about healing the sense of betrayal that I felt from the [queer] community after experiencing abusive relationships. The theme of healing is prevalent because that’s exactly what I was trying to do: process my thoughts and feelings in a chronological order, which is how it’s presented in the book. In the book, you can really see that healing is truly not something that is linear.

Can you speak on the title of the book? Why was this the right title for this poetry collection?

To be absolutely honest, it’s one of those things that came to me very impulsively when I initially put the manuscript together.

What it really comes from is the fact that I’m not out to my family. My parents don’t accept my queerness. And so when I talk about my queerness [with others], I always have to throw in that caveat of, “don’t tell my parents, don’t let my family find out.” I want to openly platform queer South Asian narratives because we deserve visibility and we deserve for our issues to be understood on a broader level. But I do that by putting myself at constant risk of being outed to my family if any of my work gets back to them.

It’s a book that intends to say, “Hey, I wrote a book about being queer. Please actually don’t tell my parents.” It is a legitimate request. And it also doubly functions in that way to say I am someone who exists while not being out to my family, but I openly exist as a queer person as well. And those two things can coexist. What we often see is this narrative that people who are in the closet, per se, shouldn’t be openly talking about their queerness. Or it’s just not understood: “How is it possible that you’re openly talking about your queerness if you’re not out to your family? Either they should accept you or you should step away until you’re ready to come out properly.”

I’m not willing to do either of those things. I’m asserting my presence as somebody who refuses to come out to my parents, and putting the onus back on people who are receiving my work and receiving me as a human in the world by saying, “It’s not up to me to hide my queerness from my parents, it’s up to you to keep your mouth shut and not tell my parents that I’m an openly queer person.” My identity is not gossip. And my queer identity is not something that needs to be told to my parents by anybody other than me on my own terms when I feel like it. And that does not mean I have to hide who I am in the world. It just means that I navigate different spheres of my life differently. And that can still mean that I’m living authentically.

What’s been readers’ response to the book? Can you speak on its impact?

The most common feedback I’ve heard is that there’s a lot of raw emotion that people really resonate with, and it really speaks volumes to a lot of folks. It’s helped people in terms of just learning to recognize when you are in those situations of abusive or toxic relationships. Many people don’t realize that toxicity while they’re in it. You kind of go through it, you endure it, and [the book explores] why that might be. The element of heartbreak and losing yourself in relationships is another point that people are able to really resonate with, even people who don’t identify as queer or South Asian.

I’ve also heard a lot of feedback about how this is a really good educational resource, which I didn’t expect when I was writing it. It was so much about self-liberation, but to know that this comes across as something that is an educational resource about what it’s like to be queer and South Asian is very helpful to know; it’s honestly just really good on the heart to know that something I did serves as an educational tool for people to understand our experiences.

Often, especially in the broader queer community, queer South Asian narratives are not heard even though there are so many South Asian people in Canada and North America. We’re severely invisibilized. And we’re not really seen as a group whose narratives people often go out of their way to understand. We’re generally just grouped into this, “Okay, you’re just a broader POC.” People don’t want to understand our culturally unique experiences, and that is a problem. So the fact that [Don’t Tell My Parents] is being understood as an educational resource to understand the queer South Asian experience specifically, that is great feedback.

Has this book impacted your advocacy efforts at all? Did writing and publishing shift your perspective in any way?

My advocacy initially started off at a point where I want the broader White queer community to understand South Asian narratives. A lot of my work initially started off by problematizing the way queer South Asian people are treated by the White community.

When putting this book together, it was actually really hard for me to even come to the point of accepting that it is okay for me to publish this. Because within the book, I am problematizing issues and the way that I’ve been treated by other queer South Asian people and within my own community, which is why I talk about the theme of betrayal. And why that betrayal hits so deep is because it came from fellow queer South Asians, it came from South Asian family members, and the broader queer community too.

And so for me, it shifted my advocacy in the sense of [realizing] it’s okay for me to also problematize things that occur within [the queer South Asian] community and that we can address it; we can bring in and implement that lens of saying, “We need to be kind to each other and we need to address issues within our community, in conjunction with mobilizing our needs and issues in the broader [queer] community.”

What are you most proud of with regards to being a published author?

This book is single-handedly the accomplishment that I’m most proud of in my entire life, for many reasons.

Since I was a kid, I’ve always wanted to write a book. I didn’t know what I wanted to write a book about, but I knew I wanted to write a book. And so my inner child is very, very happy and proud of myself.

Another reason is that the experiences I talk about are literally the worst time of my life. A time that I did not think I would live through. I didn’t think I would survive it. The only thing that kept me going was hope. And the only healing [practice] I had was writing, because I felt so damaged and my brain wasn’t functioning. It got to a point where I couldn’t have a job because I was struggling to finish my master's thesis. I was living out of my savings, and therefore I could not afford therapy.

And still, at the hardest time of my life, I did something that I am very proud of. I was able to not only write through it and eventually work towards overcoming it, but I put it into a packaged product of a book, which is a goal I’ve always wanted to achieve. I can look at this book, and say, “This is [about] the most difficult time of my life, when the most growth occurred in such a short, compact amount of time.” And I made it. I survived. I lived. I did it.

I knew I was in such a period of darkness, and there was something in me that said, “I am going to see it across to the other end. I know that I will one day.” And now I’m here, and I’m tearing up as I’m speaking because this book is me coming across to the other end. And that’s not to say I haven’t been in difficult situations since. But it’s still to show that I lived through it. I wrote through it. I have concrete proof in front of me that I can overcome anything. I can work past and let go of that trauma that really held me down for so long.

If folks reading Don’t Tell My Parents could take one thing away from the book, what do you hope that is?

On the educational side, I hope people take away that there exists the ability to peacefully coexist as someone who is both in the closet and experiencing queer life as openly as they want, and not judging or shaming that. And really being able to move past closet-shaming narratives and understanding that we need to stop enforcing this “just come out to your parents, come out to your family” narrative, because it is really deeply damaging to our mental health.

In one of my poems, I write that being told that we need to leave our blood family if we want to be queer properly is no different than our blood family telling us that we can’t be queer because we have to choose family. So it’s really being able to understand that you can coexist as a queer South Asian person and as a queer person who’s closeted, and letting us just be and live without any sort of pressure to be some identity in a particular way.

Are you working on any other book-related projects at the moment? What’s next for Alyy Patel?

Currently, no concrete book-related projects. I feel like when I tell myself, “I'm going to write another book,” I find myself stagnating.

For now, I am really focusing on my academic project, so I’m conducting new studies — actually, a study about queer South Asian women’s experiences in the closet. In addition to that, I’m working to publish other [academic] work and continuing my nonprofit work. I run an organization called the Queer South Asian Women’s Network, and I’m continuing to build and expand that organization.

You can follow our nonprofit socials @QSAWNetwork and my own @AlyyPatel. On TikTok and Instagram, I am going to also start putting out more active resources and educational videos on existing as a queer South Asian person, so you can follow that.

Aside from that, Happy Pride, Pride Mubarak, Pride Vaalthukkal, and Shubh Pride to everyone celebrating. And I genuinely hope that people are continuing to recognize queer South Asian existence as valid.

###

Don’t Tell My Parents available now.

Visit alyypatel.com to learn more.

Follow Alyy Patel on TikTok and Instagram.