Indigenous Story Spotlight

/As an author and creator, the act of publishing one’s story for others to read is a powerful act; for people in groups whose voices have been historically silenced, this act can even feel revolutionary.

We at FriesenPress have the privilege of helping many Indigenous authors share their stories in the form of beautiful, professionally made books. Their diverse titles range from tender children’s stories and poetry to thought-provoking fictional and nonfictional accounts of Indigenous life. A generosity of spirit and a willingness to help others deepen their understanding of Indigenous cultures and their core values unites these authors.

This National Indigenous History Month, we’re continuing our tradition of highlighting the authors of Indigenous-focused books with an update to our Indigenous Story Spotlight. We’ve added some new insights behind the stories, shared in the authors’ own words.

We hope this list provides you with an opportunity to reflect upon and learn about the history, culture, and strength of Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) Peoples and their multitude of stories.

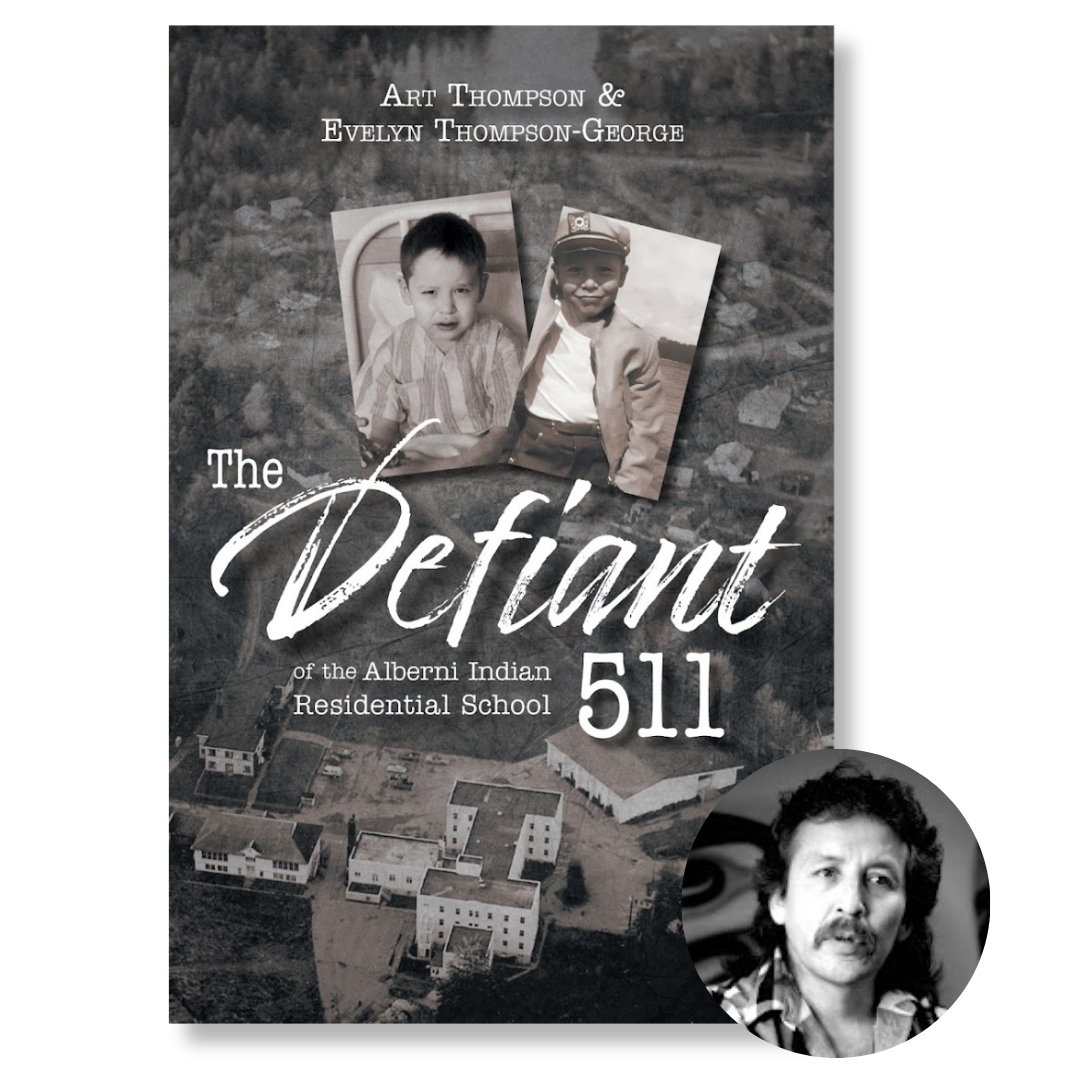

Evelyn Thompson-George and Art Thompson, The Defiant 511 of the Alberni Indian Residential School

The Defiant 511 of the Alberni Residential School is based on my father Art Thompson’s lived memories in a Canadian Indian Residential Institution in the 1950s and ’60s. From what I have learned from survivors of this particular institution, it was one of the worst in Canada. I took my father’s documents from his 1995 provincial court case and his 1999 Supreme Court case against Arthur Henry Plint, the Government of Canada, and the United Church, and used his paperwork to create a memoir of his experiences. This book was one of my father’s final wishes before he passed away in 2003. He was a loud advocate for survivors and wanted people to know the dark history of Canada; the history that so many people did a good job at covering up. This memoir gives a clear message of one survivor’s memories in an institution that was meant to assimilate him and strip him of all those special things that make us the First Nations of Canada.

I decided to publish this memoir after our first recognized National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, on September 30th, 2021. I had been asked to write a piece about my father that would be shared publicly on the former grounds of the Alberni Indian Residential School. For weeks afterward, I was receiving thank-yous from strangers. The two types of people that impacted me the most were those that were family members of survivors who had not shared their stories and from strangers that “had no idea something like this was happening in Canada.” It dawned on me that, just because my life was surrounded by conversations and healing from these institutions, it didn’t mean that was the general case in most First Nations families. The shame that was laid upon these children at such a young age was profound — enough for them to not share themselves after having left those schools.

My hope in publishing this book is to have it in educational institutions nationwide, if not also across America. I have come across so many youth that are ready to use their voice against this injustice that was given to us as First Nations of North America, Canada, and America. I do not fault anyone for not knowing about the residential school system in North America, but it is time for education, listening, and understanding.

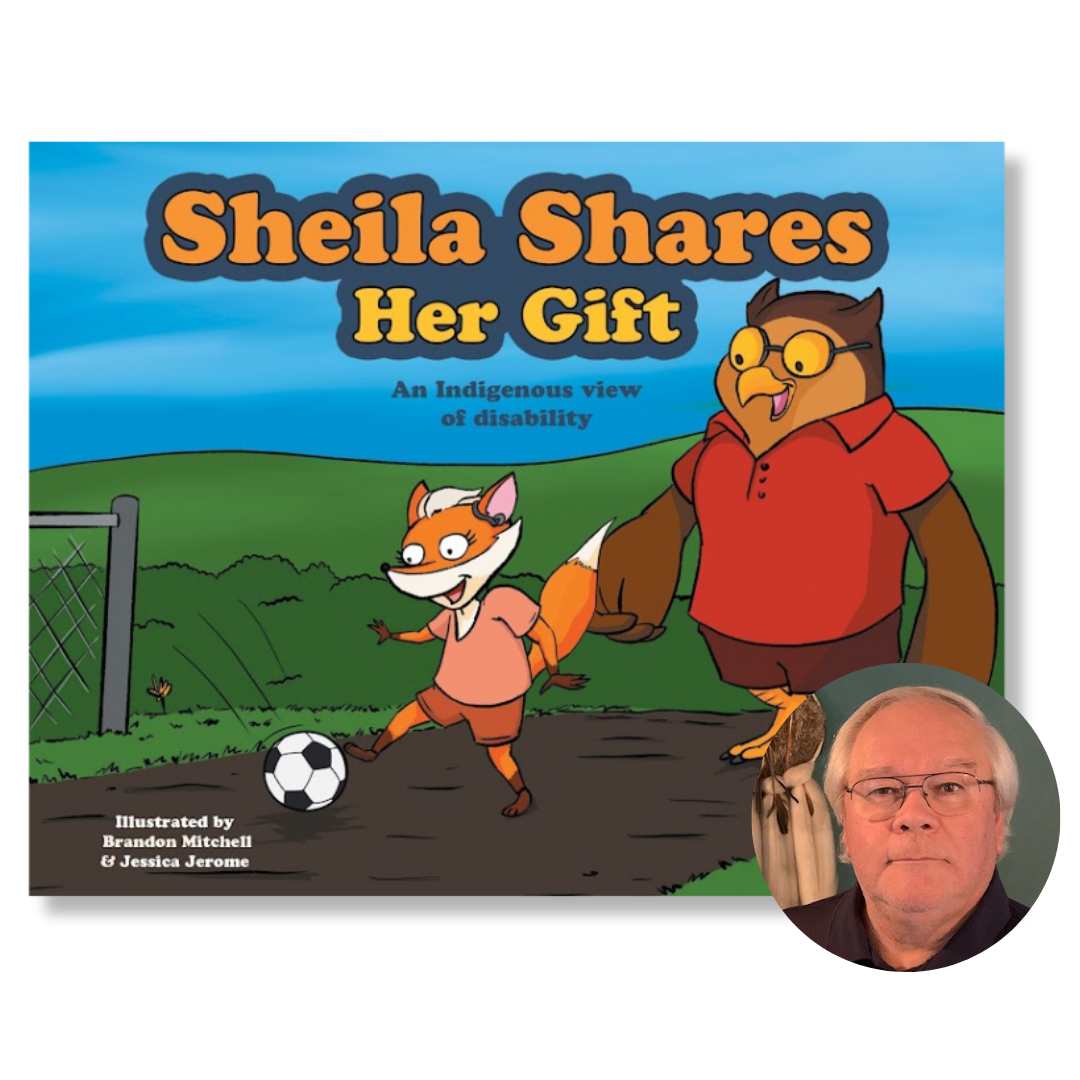

Conrad Saulis, Brooke Tracy, and Michael Hennessey, Sheila Shares Her Gift

The inspiration for Sheila Shares Her Gift came from Conrad Saulis, an Indigenous Elder and advocate for Indigenous persons with disabilities. He worked with Wendall Nicholas and Sheila Johnson who were instrumental in founding the Wabanaki Council on Disability, a grassroots organization passionate about advocating for Indigenous persons with disabilities in the Wabanaki Territory (Atlantic Canada).

Conrad envisioned Indigenous stories about children with disabilities being added to the children’s storybook community. A partnership was formed between the WCD, Mawita’mk Society, Ksalsuti Wellness Resources, and author/illustrator Brandon Mitchell to bring this idea to life. “We want to increase awareness and knowledge that children have regarding children with disabilities,” Saulis says. “They are children with abilities who can and want to participate in things with other children.”

Sheila Shares Her Gift introduces Sheila and Wendell to Turtle Island. They help kids learn that we are all different and all have special gifts. Through the children’s welcoming attitude and desire to learn how to communicate in sign language, Sheila feels included as part of the social group and cared for by the Elder, Wendell. The characters of Sheila and Wendell were inspired by the founders of the Wabanaki Council on Disability.

Our goal was to write a story not just about persons with disabilities, but voiced by persons with disabilities. The aim was also to teach kids an Indigenous view of disability. Originally, Indigenous communities did not consider individuals with various life circumstances and realities to be “disabled.” Rather than focus only on different needs, each individual is unique and brings specific gifts for the benefit of the community as a whole. As Conrad voices, “Our ancestors didn’t see anyone as having disabilities, but [rather] everyone having abilities.”

Learn more about the Mawita'mk Society here | Browse the book on our bookstore

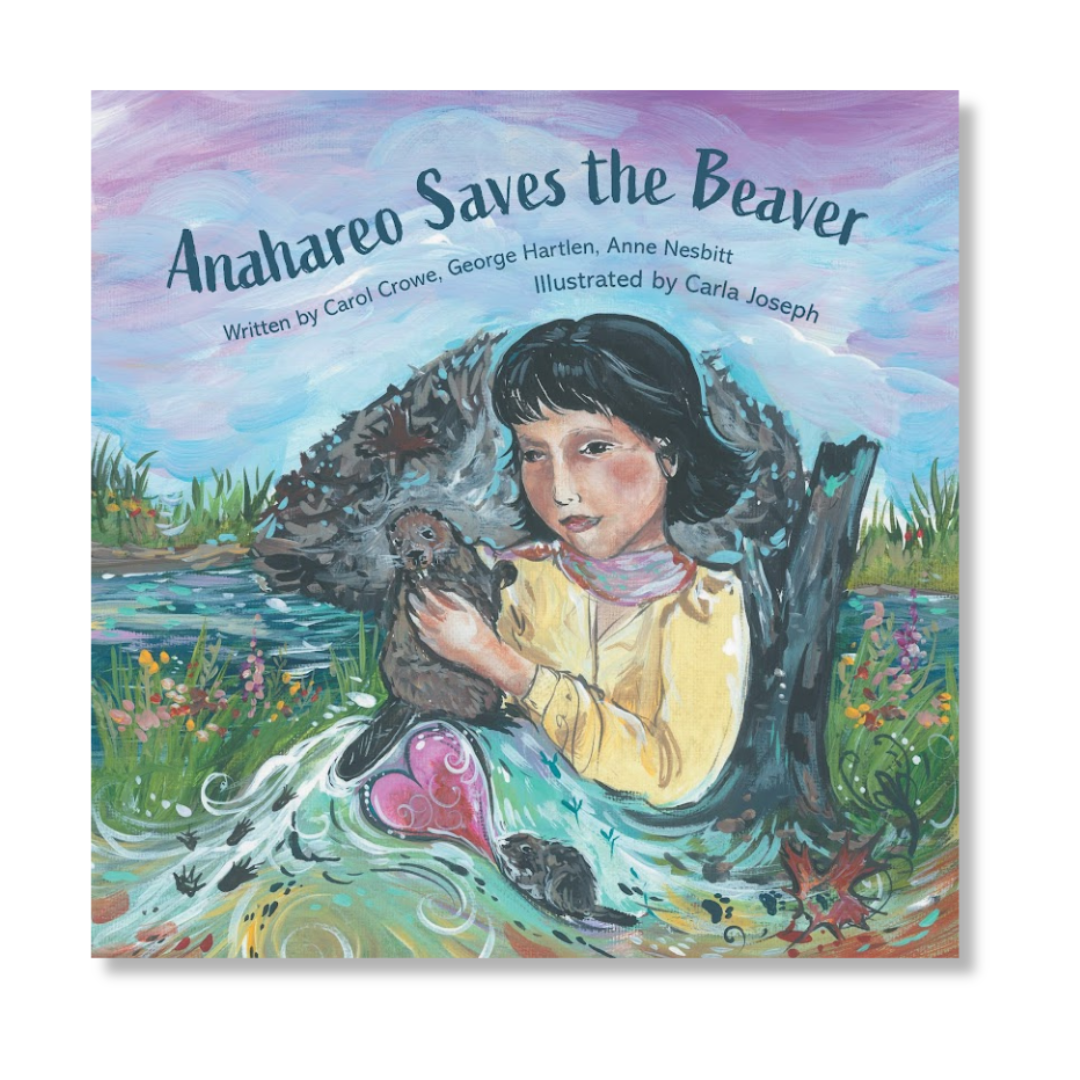

Carol Crowe, George Hartlen, and Anne Nesbitt, Anahareo Saves the Beaver

Anahareo Saves the Beaver is more than just a children’s book—it’s a legacy project.

The book tells the true story of co-author Carol’s Auntie Anahareo, a trailblazing Indigenous woman whose compassion and courage initiated the conservation movement in Canada and around the world. Anahareo helped save the beaver from extinction. However, most Canadians have never heard of her. We wrote the book, Anahareo Saves the Beaver, to change that!

Recognizing the importance of Anahareo’s story, we approached the publishing process with care and cultural intention ensuring that it authentically reflected Anahareo’s life and Indigenous heritage. We focused very strongly on the illustrations, which don’t just depict scenes but breathe life into them, inspiring the reader to foster relationships with Indigenous historical figures, animals, and the land which evoke emotion, capture the attention, and spark the imagination of audiences of all ages. We were very intentional about the design of the book. We were thoughtful in integrating the text with Carla Joseph’s captivating illustrations to draw the reader into the cultural milieu and the vast expanse of the land. This captures not only the spirit of the story but the spirit of the land itself. Carla’s endearing images inspire a relationship and empathy with the environment, in readers, which launches them on their own journey of environmental stewardship.

What began as a tribute to a forgotten hero has blossomed into a wonderful adventure, spiralling us out to connect with children of all ages, as well as adults and seniors. The book now serves as a dynamic tool for education and reconciliation and creates a platform for sharing Indigenous environmental wisdom. Our presentations are inspiring discussions about the principles of Indigenous environmental stewardship that were so evident in Anahareo’s life and are now intensely relevant to our lives, today, when environmental awareness is more urgent than ever. The project is continually offering a reconciliation opportunity that invites us all to learn, grow, laugh, have fun together, and share our experiences with the world. We are ever aware that Anahareo Saves the Beaver isn’t just a story from the past. It’s a call to action for today.

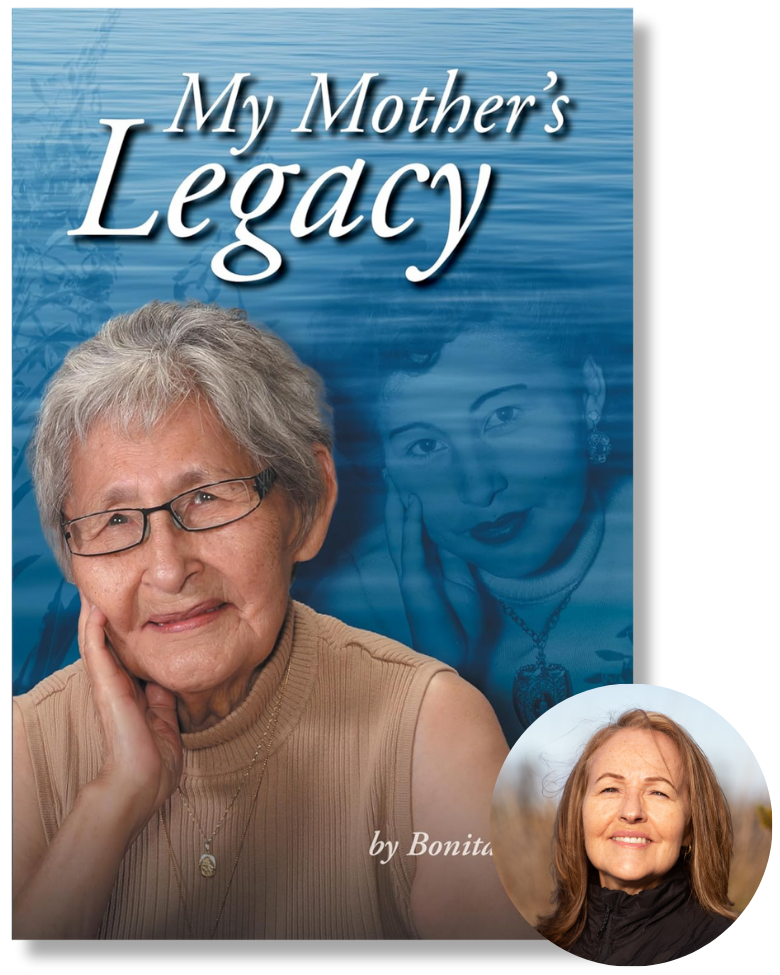

Bonita Nowell, My Mother’s Legacy

My Mother’s Legacy is a survival story and celebration of the life of Angie Mercredi-Crerar — my mother. From life on the trapline in the Far North to meeting the Pope at the Vatican, her journey is one of perseverance and triumph. Many years ago, my mother promised her father that she would take care of her younger sisters and help others. I made a promise to my mother and my siblings that I would share her story.

This book is a gift for my mother and siblings and is dedicated to my mother, with love. It is my hope that my book creates greater awareness and understanding of Métis People in Canada by sharing a more personal reflection of traditional Métis values of family gatherings, humour, honesty, loyalty, music and dance, pride, respect for Elders, storytelling, sharing, religion, and food.

By having my book available through public libraries, university and college libraries — where several have indicated they are also using it as a reference for Indigenous Studies programming — I am contributing to the body of Indigenous works that are, in the words of author Gregory Younging, “an extension of Traditional Knowledge systems, Indigenous histories, histories of colonization, and contemporary realities. Indigenous Literatures frame these experiences for Indigenous readers and provide non-Indigenous readers with context for these realities.”

Visit the author’s website | Browse the book on our bookstore

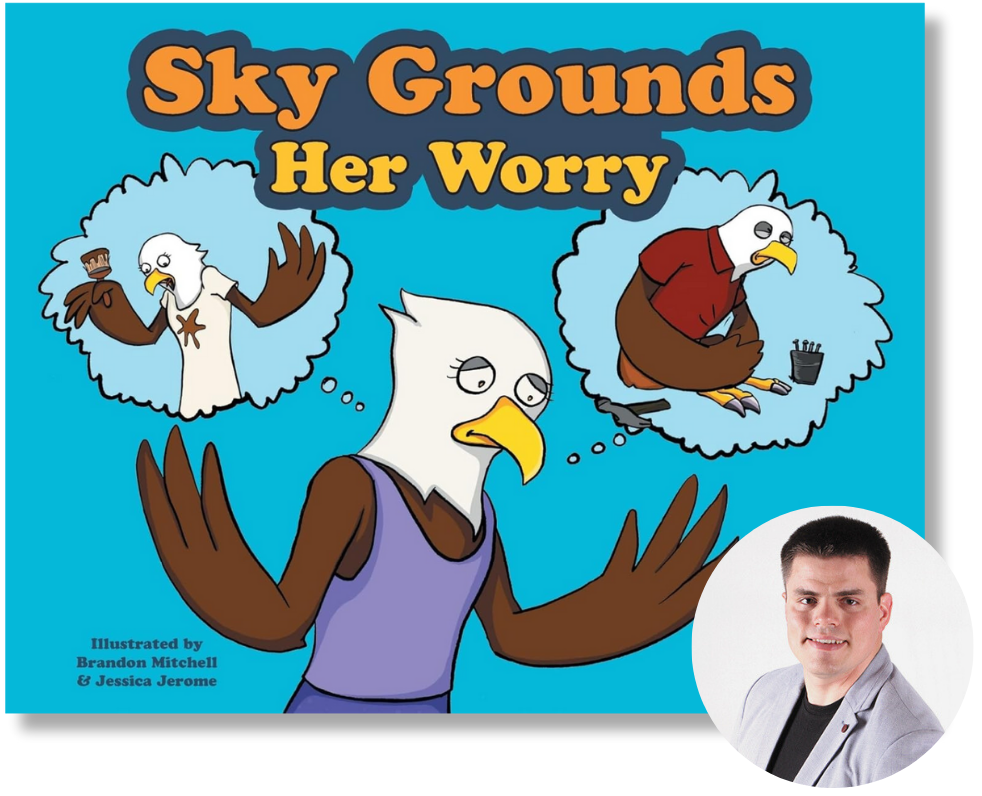

Mike Hennessey, Sky Grounds Her Worry

My clinical work as an Indigenous licensed counselling therapist in the province of New Brunswick has always been a passion, considering the intergenerational trauma experienced by my own family and community of Pabineau First Nation. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, my colleague Rachel and I were abruptly cut off from face-to-face interventions with clients. This included a large proportion of Indigenous children in the Wabanaki Territory (Atlantic Canada) aged 4–7 years old. Virtual counselling was not an option for these young Indigenous children, so we searched for resources and stories that helped address the major challenges we had been observing in our clinical work at that time. We intended to share these resources with caregivers. Unfortunately, there was a dearth of content intended to support the social and emotional wellbeing of children and families from an Indigenous lens. That’s when it dawned on us to write our own stories. We developed the world of “Turtle Island”, with each child character reflecting an aspect of the Seven Grandfather Teachings, along with Dawn the Beaver, symbolic of wisdom, who was to be our Elder and teacher.

Sky Grounds Her Worry is a story specifically written to give children grounding techniques through a story written and illustrated from an Indigenous lens. The main character is an Eagle (“gitpo” in the Miigmaq language), which is a symbol of “love” in the Grandfather Teachings. However, a loving eaglet named Sky is still learning how to care for others without being overwhelmed by worry. This tale demonstrates one strategy to use with children to help them remain grounded in the present moment, connected to the Earth and their own bodies, so that fear and worry do not overwhelm them.

Illustrated by two Miigmag artists, Brandon Mitchell and Jessica Jerome, we hope that Sky Grounds Her Worry is a helpful resource for children and caregivers from all backgrounds. It is also available in the Miigmaq and Wolastoqey languages.

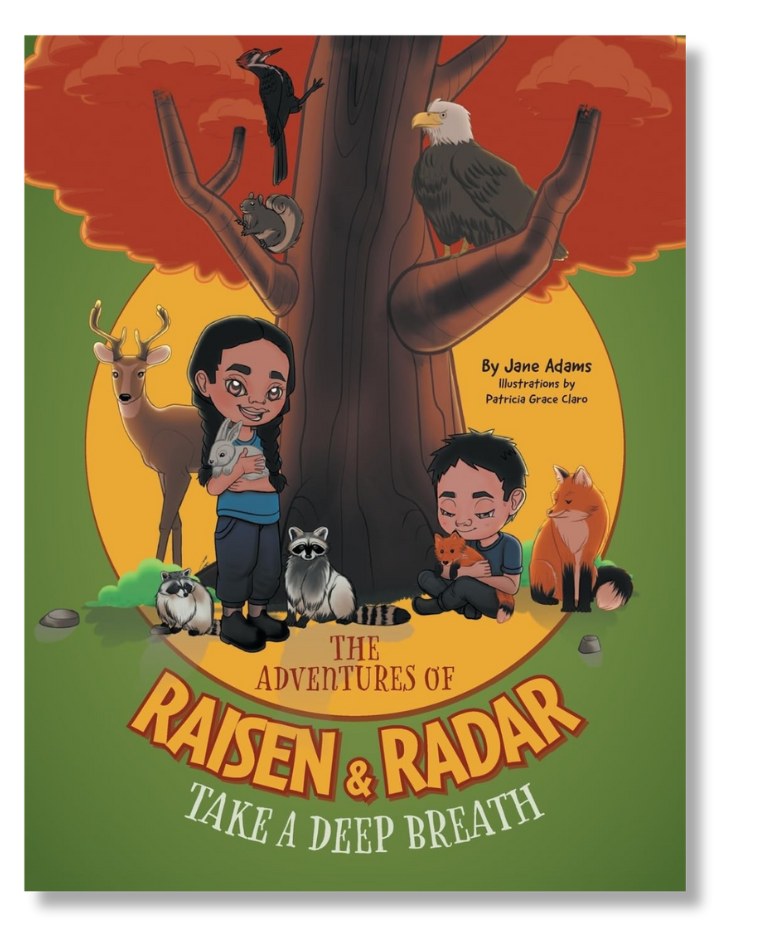

Jane Adams, The Adventures of Raisen & Radar

I have had the privilege of learning so many Anishinaabe teachings from being a member through my marriage. Western society tried to stifle our culture using residential schools and pushing to be like Westerners. The Indigenous people stayed strong and made sure to keep their teachings and culture alive in all communities. I’ve personally connected in so many ways. Through nature, song, healing. The sun, moon, and the land. Animals, birds, and trees. Each and every element that surrounds us has meaning and guidance. This beautiful Indigenous culture opens the door to see it.

When I became a grandmother of two amazing people, I wanted to share their culture with them. As they are very young, the way to pass this knowledge on came to me via a children’s book: The Adventures of Raisen & Radar.

The book is about two young children who honour and share in their Anishinaabe culture. They walk and share in nature’s wonders. The book is full of imagination, colour, and some language. Each of the four stories carries a teaching of the Anishinaabe people. Raisen and Radar let others into their world and culture — take a walk with them!

Visit the author’s website | Browse the book on our bookstore

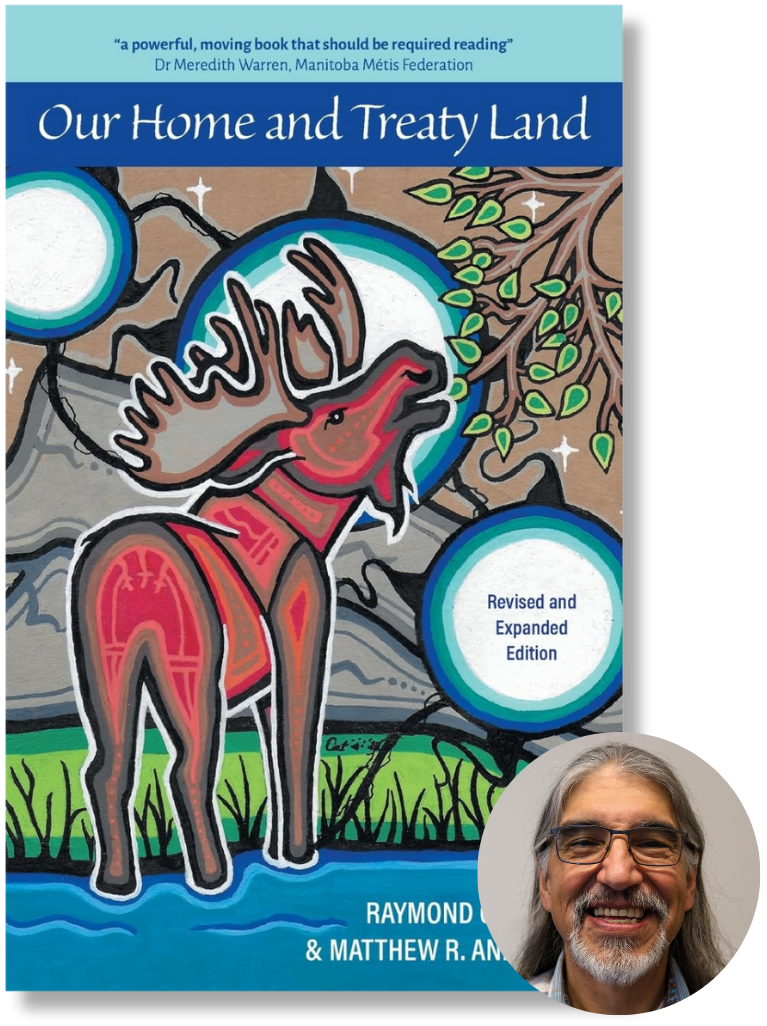

Dr. Ray Aldred, Our Home and Treaty Land

What [my co-author] Matthew and I were trying to do with Our Home and Treaty Land was to give a visible expression of what it means to walk the circle of the earth together in a good way. We set the book up so that we go back and forth, discussing what it means to live out our creation stories. We have been placed on the earth in shared space. In our modern world, when land becomes contested, people react to their fear by trying to build bigger walls, buy more guns, or better locks, or have more police. We followed the ancient wisdom to locate confidence and freedom in the sharing of our relationship with the earth. If the earth is our relative, then we can embrace the things that come from the earth: food, medicine, shelter, and identity. If you think about these things and Canada, we were pointing out how newcomers, through a relationship with Indigenous people, have a relationship with this land. The treaty, the relationship, is with Indigenous people and the land. On the land, we have the opportunity to think and feel and experience the things that our ancestors felt, thought, and experienced on the land. We wanted to cast a vision of unity that was held together by the land as we shared this space where we lived out our spirituality.

Visit the authors’ website | Browse the book on our bookstore

Pearl Long Time Squirrel, Sacred Bird

I have always wanted to write the stories I heard when I was younger, but the opportunity to publish one never occurred until I retired. Not knowing how to publish a book was a challenge. I wrote Sacred Bird when I had free time. I also wrote it with the encouragement of my cousin, Carrie Hunt. Carrie was the last person to hear the story [orally] and she thought it was important for the story to be written down for future generations before it was lost.

During my discussions with Carrie, some very important points were brought up: today’s generation is “too busy” to sit and listen to stories, and the majority have lost their ability to speak and understand our language. As a result, they do not know their identity or their proud heritage. Some have “adopted” other nationalities’ ways and demeanours. This was very concerning for Carrie. Carrie and I wanted to give the younger generation an insight of the hardships and traumas experienced by our ancestors and their survival skills. Lastly, to inspire others to share by writing the stories they have heard.

I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to FriesenPress for their support and guidance throughout the process of publishing Sacred Bird.

Mallory Eaglewood, Throwaway People

In my book, Throwaway People, Birdie’s carefully cloistered world breaks wide open when she finds the body of a fisherman washed up on a Scottish beach, reminding her of the brother she lost when she was 11. Her parents threw him away, and she never knew what happened to him. Decades ago, she’d fled abuse and she felt the doors closed to her for both her Native and White ancestry. Now, it is 1995 and at 59, she returns to Canada for answers. But to do that, she must walk through a minefield of racism and betrayal, as well as her own guilt and lack of confidence, to find her brother and her own identity, somewhere between Native and White. Balancing fear and determination, Birdie’s exploration of her tortured past puts her in the path of an unknown assailant who wants her story buried, along with her.

This story is my healing song, and my wish is to make generational trauma caused by the Residential School experience part of our national historical narrative. As my Native Gramma, a residential school survivor, used to say, “when one part of the circle is ill, the whole circle is ill.” Publishing Throwaway People is my humble attempt to give her a voice and the respect she was denied while living.

Visit the author’s website | Browse the book on our bookstore

Mark Thunderchild, Our Journey to the Dentist

This book’s inception started with an off-chance meeting in an elevator. Luckily, by that point in time, my elevator pitch for my first book had become refined.

That conversation birthed the opportunity for my children’s books to support the Indigenous Dental Association of Canada with their work with the Federal Government and Indigenous oral health.

Using my positive modern Indigenous living genre, the Indigenous Dental Association of Canada and I were able to create a fun normalization of First Nations people and Indigenous oral health in the form of Our Journey to the Dentist.

This book is not so secretly three different stories of the diverse ways in which I grew up in Indigenous Canada: I’ve lived in Nunavut, the north, and in the city. I have always had to travel for my health and dental needs. Each of these stories were very easy to draw on; for the mandate of this book, I just had to tell my story. Because of my diverse background, it’s the same story told through three different Indigenous circumstances.

Working with Dr. Sheri and Andrew McKinstry to promote Indigenous health has been nothing short of amazing and fulfilling, and we look forward to getting more Indigenous language translations for this book.

Dorothy Ladd, Memengwaa: The Monarch Butterfly

I marvel and am in awe to see the incredible transformations of the monarch butterfly through their four stages. My interest led me through the process to raise, watch, and set them free for their journey to Mexico through “tagging.”

I decided to publish Memengwaa: The Monarch Butterfly to educate others through vivid illustrations and story. The monarch butterfly’s spirit is important in our culture as it connects with our beliefs in the past and future.

This book was published both in English and Ojibway. The Ojibway language is taught in our local schools, and the book aids in the children’s learning of the language. Since the Ojibway language is declining, it is a means for our Elders to reinstate it by reading to their children, too. Though this book is intended for the younger set, it can be enjoyed by all.

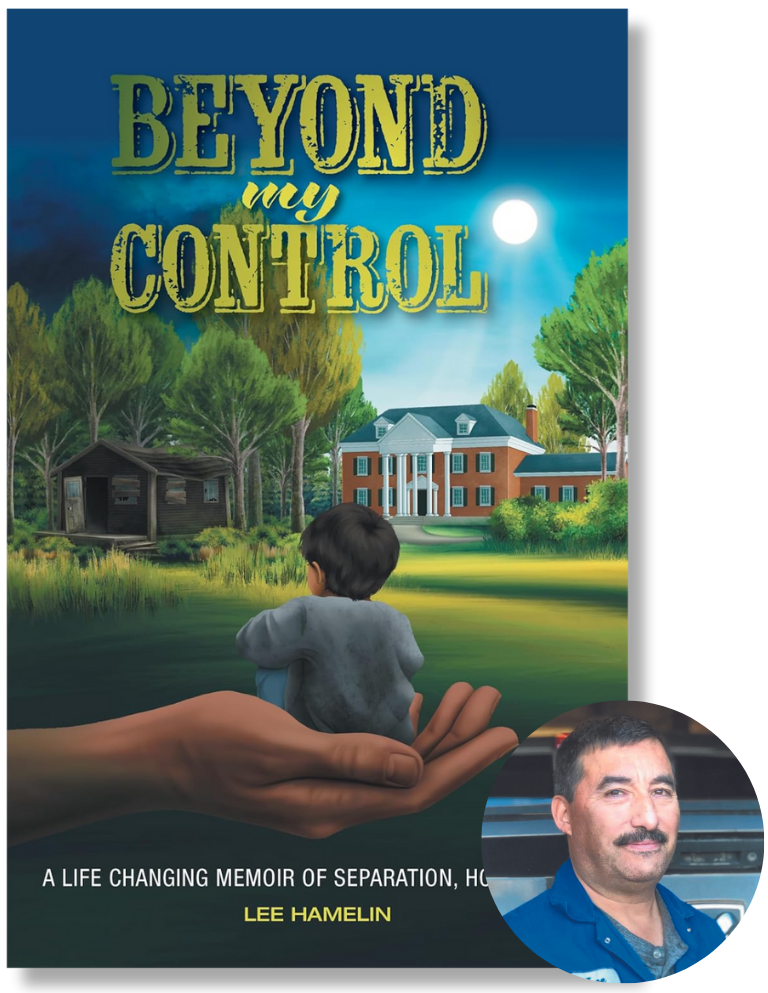

Lee Hamelin, Beyond My Control

The reason I wrote about my storied journey is to help people understand the complexity of colonization and how it affected me — and still does. There is good that can come out of the bad. Beyond My Control is about my struggle with Native identity as a person myself, not someone else’s perceived idea of what it means to be Native. Many people do not know Native history and can’t fully understand what happened until they hear about it firsthand.

My goal with this book is to change people’s perspectives on living alongside each other, the less fortunate, and Indigenous peoples.

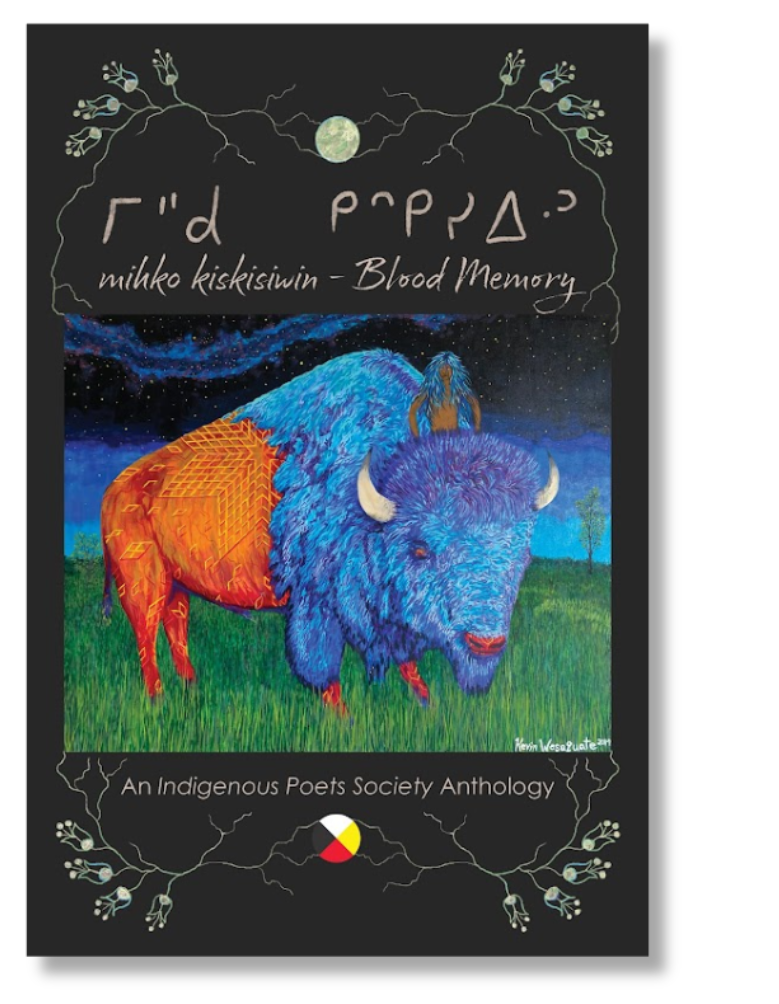

The Indigenous Poets Society, mihko kiskisiwin

The “Blood Memory, mihko kiskisiwin” project came into existence to breathe life into Indigenous ways of poetry through spoken word and storytelling. Indigenous Poets Society wanted to share the rich heritage that exists all over Turtle Island in storytelling the oral tradition. We felt that our regular online meetings with the Indigenous Poets Society could be so much more.

The idea to share on a monthly basis had existed firstly in our monthly Spoken Word competitions and community stage experiences. When the pandemic hit, we were forced to write and share from the confines and security of our homes.

Thankfully, founder Kevin Wesaquate had already established connections out east with the Guelph Poetry scene and had the privilege to meet Hope Engel from Plume Writers Circle. This union began when we co-facilitated “‘Write’ Relations” writers collective on Zoom during the pandemic, and Hope asked if Plume Writers Circle could join and become part of Indigenous Poets Society, so that we could have Indigenous Poets Society spread and reach across Turtle Island. We heard from amazing writers across Turtle Island and decided to collaborate and create this anthology.

Kevin suggested that we title the anthology mihko kiskisiwin, roughly translated to “Blood Memory,” which is a recognition that our stories from the past live through us genetically and through our language and lived experiences. We are here as Indigenous storytellers and poets to relay the oral traditions of the past. And most of all to encourage others to share and be proud of our writings. Together we collaborated to create this anthology. We have formed a great working partnership from Saskatchewan to Ontario that is sustained to this day to empower the artistic, storytelling, and literary voices of the people across our various nations and communities.

Visit the authors’ website | Browse the book on our bookstore