A Life in Film: How Prop Master Dean Goodine’s Memoir Became a Blockbuster

/Dean Goodine has a knack for storytelling — in more ways than one.

He’s been an in-demand property master (“prop master,” for short) on film and television sets for the last three decades, bringing his expertise and keen eye for detail to projects like Inception, Paschendaele, and The Edge.

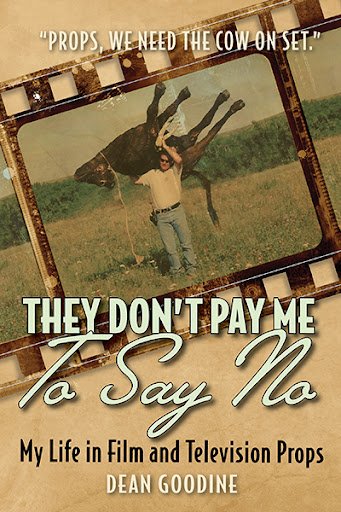

This past summer, Dean proved that his storytelling prowess isn’t limited to the visual medium by publishing a book. His first memoir, They Don’t Pay Me to Say No spans the highs and lows of the 30+ years of filmed media that Dean has helped bring to life through his unique on-set role. As Dean explains, his is one of few non-how-to books written by the blue collar workers of the film industry: “I didn’t want to write a how-to book, because props is not a how-to [industry]. Every day is different.”

The surreal, humourous cover photo sets the tone for the pages to come; in it, Dean is posed with what appears to be a farm cow — raised completely over his head. But, as you’re about to find out, nerves and self-doubt almost resulted in this now-bestselling book to be left on the cutting room floor.

We spoke with Dean while he was taking a break on the set of an upcoming Disney project to learn more about They Don’t Pay Me to Say No, including what it’s like rubbing elbows with Steven Spielberg on a bestseller list, the importance of leaving a legacy for future filmmakers, and much more.

After so many years behind the camera, how does it feel to have stepped into the spotlight with this book?

As Lee-Ann and my team at FriesenPress will tell you, it isn’t the most comfortable feeling to put yourself out there in writing a memoir — especially for somebody who spent 37 years behind the camera. Although I was very easy to work with, I was also very nervous and reluctant at first about even doing this — to the point where, a couple times, I thought “maybe I’ll just stop.” But [my team was] really encouraging and kept me going.

I have to admit, although the book’s been out for a few months, it’s just in the last month that I have finally embraced it to the point where I now want to try and get more word out about it. Before, I was almost trying to keep it a secret.

What motivated you to overcome your nerves and publish They Don’t Pay Me to Say No?

After I wrote the manuscript, I sent it out to some conventional publishers, not really expecting anything back. I just wanted a little bit of feedback, because I really didn’t know what I had. And although the book was passed by everybody — because [publishers didn’t] really understand who would want to read a book by a prop master — I’d had a really nice letter back from a publisher. It said, “Look, we think the book’s good, but it doesn’t really fit our catalogue. We only publish 20 books a year.” But it was an encouraging letter.

I had two thoughts. [A] “They write nice rejection letters to people so that they don’t feel too bad,’ and [B] “Maybe there is something here.” And so I put it on the shelf. I just didn’t know what I was going to do with it.

And then the Rust tragedy happened, where [cinematographer] Halyna Hutchins was tragically killed in New Mexico. I realized the one thing that our industry has always been founded on (at least of my generation) was mentorship. We always had really strong mentors that guided us through the process of navigating what has become a long career. In the last seven or eight years, with the growth of streaming content and shows, a lot of people have been promoted so quickly that they haven’t had the foundation of mentorship.

I went back and reread my book again and realized that I had to tweak some of the writing to address some of the issues that were happening on the sets. Soon after, I happened to be on set for a movie, and I picked up a book by another prop master about sailing. His name is Dean Eilertson — his book is called Dreammaker, and we were using it in the movie as a prop. I opened it up and looked at it, and saw that it was published by FriesenPress. Ironically, he has the same first name as me, but Dean is a very meticulous prop master who I know does all his research. I thought if he decided to go with FriesenPress, then they must be a really good company. I did a little bit of research myself, and that was when I decided I was going to self-publish. I did not want to send it back out to publishers for another round.

When did you start writing?

I started working on it in early 2020. I was working on a movie with Sandra Bullock called The Unforgivable at the time.

I’d been journaling for years on my Facebook page, telling funny film stories. People kept saying, “You should write a book.” I’d never really taken them seriously because writing a book was never anything that I had ever thought about. While I was doing that movie, one weekend I just started writing, and I found it so helpful to put my brain somewhere else besides the movie. I wanted a distraction.

I completed the first draft in six weeks, about the first month into the pandemic, in April 2020. Next, I sent it to a friend — a very accomplished reader — who sent it back to me and said, “Well, it’s pretty good, but you have to put yourself in it.” I’d written a memoir without me in it — other than telling some self-deprecating stories.

I went back and, over the course of another month, I wrote another 30- or 40,000 words and put myself in the book (which I didn’t want to do) and sent it back to him. “Well, now you have a book.” I spent another 18 months rewriting, and then I sent it to you guys [at FriesenPress]. Everything took off from there.

What’s been the response from readers so far?

I’m very terrible at taking compliments. But the response amongst my peers and people who work in the [film] industry — it’s been overwhelming. And even from some people who don’t work in film at all.

I didn’t want to write a how-to book, because props is not a how-to [industry]. Every day is different. We don’t know what we’re going to face every day. We’re always solving problems or trying to anticipate them by prepping to not have any problems. When I wrote the book, I was really trying to make sure that anybody could read it, and anybody could pick it up and put it down.

It’s kind of a series of short stories. Every experience on a set is a short story in its own right. I really enjoyed reading Bill Bryson’s books, and I really like listening to Stuart McLean. I really tried to put a little bit of that into the book. When I hear from people all around the world, from Australia and from Los Angeles, it’s been quite amazing. An 87-year-old retired prop master who’d done Patton and Papillon said if he were to write a book about props, he wouldn’t have anything to say because I said it all — which is probably the best compliment.

You’ve expressed amazement on Twitter whenever the book hits a new sales milestone, such as ranking #1 on Amazon in the Film Production and Direction categories. Is it fair to assume you never envisioned your book doing this well so quickly?

Not at all. As a matter of fact, FriesenPress has such a good program — you ask authors “what are your expectations of your book” in one of your first questionnaires.

My goal was to sell five copies to people I didn’t know. That was my goal because your friends and family will always buy the book and tell you it’s great, because that’s what they’re supposed to do. To go from that goal, to now seeing it on a bestseller list next to Steven Spielberg and George Lucas or Francois Truffault or Terence Malick… It still doesn’t feel real.

You’re going to have to keep a screenshot on your phone next time any director gives you a hard time on set.

Trust me — I have a lot of screenshots. I want to keep a record of when it was number one on Amazon in the USA or number one on Amazon Canada.

Last week, Chris Nolan and I were together on the bestseller list. The fact that I worked on one of his sets for nine days — it wasn’t lost on me that I was suddenly on a list with Christopher Nolan.

I’m having a hard time talking about it because it still seems like I’m talking about somebody else.

You’ve helped bring so many stories to life on the silver and small screens. Did your background in film and props help you during the writing process at all?

Pace is very important. Working in film for over 30 years, you become very aware of pace and when you’re bogging down. The hardest part of the book for me to write was the intro, because suddenly it was like doing the dry stuff. “This is what a prop master does.” “We do this, we do this.” I really wanted to get to the stories, but the friend who critiqued my book told me I had to [write the intro] so people understood what the job was before diving in. It was the hardest part because it was like, “Am I going to lose people in the first 30 pages of this book?” I really wanted strong pacing after that.

And I wanted people to smile. I wanted people to feel sadness. I wanted people to feel the emotion that I was feeling in the middle of a scene because [prop mastering is] truly an amazing craft that nobody really knows much about. We’re with the actors all the time. We help them become their characters through the items we place in their hands. I’m there for rehearsals, I’m there watching the character develop before my eyes — before the audience even knows. It’s pretty phenomenal to be through that, and I really wanted that to carry through the book.

Have you done anything with marketing the book that you can attribute to its success?

I have to credit social media. I don’t have a lot of friends on Facebook, but I was smart enough with my Facebook page to stay out of politics and meanness. I’ve built a Facebook page around being what I am, which is a pretty easy going, laidback human. Because I love music, I introduce and share new artists or musicians. I tell a film story, or I post some photos. I ended up with over a thousand Facebook followers throughout the [film] industry, across North America. All were excited to hear the book was coming out.

There’s also a film website that I’m on called Crew Stories, which has 75,000 film workers on it. I posted it on there one day — which took me months to get the courage up to do — and said, “Hey, I’ve got this book.” I think at the time it was number #1200 in movie books on Amazon in the USA. And in 48 hours it went to number one. In 48 hours! Other people found it through word of mouth. It’s the type of book that might be around for years, just as one of those little found film gems like Robert Evans’ book, The Kid Stays in the Picture from [1994].

I’m pretty lucky because I work in media, so I have contacts and, through the goodwill of those people, they’ve managed to open some doors for me. The Calgary Herald did a full-page article about me and the book, and then they sent it off to all their newspaper subsidiaries all over Canada. CBC’s North by Northwest with Cheryl McKay also did 15 minutes about the book.

You mentioned that the first draft of the manuscript came together in just a few weeks. How did it feel to go from writing as stress relief to having the beginnings of a book in such a short period of time?

I was surprised at how much, how fast, and how easily it came out. And I say “easy” until [A] you put it in the hands of people who critique it, and [B] you end up with the professional editor at FriesenPress, who was really great. It was such a wonderful experience. I was desperate for somebody on the literary side to get their hands on it and go at it from an editing perspective. I’ve never seen so many red lines on a page since Grade 10 English, for all the suggestions and changes. And as I said to Lee-Ann, who was working with me, I was so grateful because they made the book better. They made it a book.

What was your level of writing experience leading up to you creating They Don’t Pay Me to Say No?

I wouldn’t say I had a lot of writing experience. I certainly don’t have a blog or anything like that. I would tell short versions of the stories on my Facebook page over the course of years. But when I started to write the book, I think I probably came from a place of some first-time writers: as a voracious reader. I tend to read a lot more magazine article–size samples of things, and a lot of autobiographies. From autobiographies, I sort of gained the knowledge of what I thought would work, and what I thought wouldn’t work, narratively. And I used that knowledge to put it down on the page.

Do you have a favourite story from the book that you’d like to share with our readers, to give them a taste of the book?

The one story that always resonates with me, because it was a real watermark moment in my career, was day one of Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood’s western. The scene was: Clint is shooting the can off the stump with an old Starr .44 pistol. And it was my first day on set with the prop master Eddie Aiona and his assistant Mike Sexton. The thing about Clint Eastwood crews is that they’ve all been with Clint for anywhere from 10 to 40 years. Nobody talks on those sets. They have a real shorthand, and I was the new guy trying to fit in.

When we were getting ready to do that scene, Eddie was trying to talk Clint into using another pistol, because that [Starr] revolver would never fire all six shots in prep. It was an old Confederate pistol. And Clint said, “Well, let me try it once, and if it works, we’ll keep going.” I took one part of the loading, Eddie took another part, Mike took another — in other words, without even talking to each other, we all just launched into our role. It went out and it fired all six shots. And it fired all six shots every time.

Fast forward to the end of the movie, and we were driving back to Calgary. Eddie said to me, “So, when do you think we came together as a department?” And I said, “Day One. The Starr pistol.” And he goes, “I thought so.” He reached into an envelope and pulled out an autographed picture of Clint firing that pistol, signed to me, thanking me for doing a good job. Because it was early in my career, I cherished and carried that moment with me for another…32 years, since we made that movie. This is my 32nd year of carrying that moment. So, that’s my favourite story out of a book of favourite stories.

Are there any lessons you learned from writing or publishing this book that other authors should know?

Believe in yourself. You’re always going to have self-doubt at first. Don’t be afraid to reach out and ask a trusted friend or family member who you know is a really good reader for their opinion. You don’t have to send them the entire book, but just give them a sample if you want a second opinion. For me, it wasn’t really until I entered into the private sector with FriesenPress and got their feedback that I knew I was onto something. Until you get it out of your hands, you’ll always find fault.

Believe in yourself, write from your heart, and try to set writing time. And make notes. If you can’t write something down in full, just make notes. When you do sit down to write, you’ve got something to draw from.

You mention that the property department is typically overlooked in the film industry and by media consumers. If readers could take just one thing away from They Don’t Pay Me to Say No, what do you hope that is?

I hope they would take away, “I had no idea how much that department does on a film set and how involved they are in everything.”

We are involved in virtually everything on a film set in some way or form, whether it’s the food in a restaurant scene, the books that people are looking at, the ticking time bomb — is that a red wire or blue wire you have to cut? It’s the map the heroes need to look at to find their way out of a situation. It’s that key photograph that suddenly changes the whole story.

That’s what we do. We are the heartbeat of a movie at times. We give it its pace and its pulse by the items we put in the actors’ hands.

I don’t watch movies for props. I watch movies for story, but at the end of the movie, I want people to say, “Wow, that prop department did an amazing job — considering I didn’t know what props was before we read the book!”

You’re still working as a prop master — do you have another book in you?

The answer is yes — but it’s not going to be about me. I pretty much said all I can say about myself. I get sick of myself at times!

My wife has had an amazing career. She worked for 40 years in the film and television industry in Canada. She’s an Oscar-nominated set decorator. She’s won a Genie Award, which was the Canadian version of an Oscar before they changed the name to the Canadian Screen Awards. I’ve been putting some stuff together to write a book about her and her career, so we’re starting that. She really enjoyed what happened with the first book — and she’s in it quite a bit, which made me realize I could expand on a lot of her stories. Because I’m working full time and we’re still plotting it out, I don’t know when that book will be released. But there is a second book coming.

There’s not a lot of books written by what I call the blue collar workers of the film set. There’s lots by directors and cinematographers and special effects, makeup, and all these how-to books. But if you look at the real workers of the film set, the prop masters, the set decorators, the key grip, the gaffers — there are not a lot of books out there about them. I feel like maybe we can leave a couple of things behind for future generations, which was really my thought with my book — to leave something behind after my long career for young filmmakers coming up. And if I can do the same thing with Janice’s book when it’s ready, we’ll do that.

###

They Don’t Pay Me To Say No available now.

Visit theydontpaymetosayno.com to learn more.

Follow Dean Goodine on Twitter and Instagram.