An Editor’s Guide to Good Citations

/I get it—I used to hate citations too. In school, I’d often stop writing just to make sure that my citation was correct before moving on, partly because I’m a perfectionist, but mostly because I was terrified of being accused of stealing information. After years of writing papers and editing others’, I’ve discovered that I like editing other people’s citations. When they’re incomplete, I get to do a scavenger hunt across the World Wide Web to find the missing information.

For longer nonfiction books, citations can be tedious and time-consuming, especially if you draw from many different types of media instead of just books and journals. Overall, my goal is to help you integrate citations into your workflow so you don’t dread doing them and make the mistake of putting them off until the end.

This article refers to the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), as it is the standard style guide in commercial publishing and at FriesenPress. This style is used for both fiction and nonfiction (but for the latter, you may also see APA and MLA style guides used).

I won’t claim you’ll come out of this article loving citations, but at the very least I’d like to show you that, with some planning and a more practical understanding, they won’t be so bad to get right.

What Is a Citation, Anyway?

A citation indicates to your readers that you’ve included information that originates from a different source. That might seem obvious but still abstract. When you’re first writing and trying to find the flow of your arguments, it might be helpful to think of it this way: The basic goal of a citation is to provide enough information for the reader to find the original source.

Rather than spending time detailing what a perfect, correct citation looks like, I suggest thinking of citations from their practical purpose. (Besides, there are plenty of resources out there regarding the by-the-book guidelines of writing citations.) If someone were to pick up your draft with no knowledge of what you’d written or what sources you used, what pieces of information would they need to find the original source of some claim you’ve made? It usually boils down to these three components:

The author

The name of the source

The date of access or publication

Your editors are also your readers! An editor can assist you in clarifying your citations, but this is only possible if we have enough information to find the original source.

Instead of worrying immediately about including all the details—especially if you find that citing perfectly off the cuff is interrupting your writing flow—you can make a note of this information and clean up the details later. This applies to writing in general: put words on the page first; you can make it better later.

Whether you use many different sources or only draw from a few, I still suggest using a spreadsheet with those three data points as columns (author, name of source, date). An additional column to paste the link for online sources is another great addition. If using footnotes or endnotes, you can make a quick note or paste the link of the source and keep writing.

Verifying Sources

As you hunt for sources, you might wonder whether a source you’re using is reputable. Here are some common things to look for when determining the reliability of your sources:

Primary, secondary, or tertiary. Respectively, these are a) firsthand accounts from a time and place, b) analyses by authors who were not directly involved, and c) an index of already published primary and secondary sources. Depending on your subject matter and goal, you will be using or relying on any number of these.

Accessibility. Sources should be easy for the reader to find—after all, the goal of citations is to point back to the original information should the reader desire a deeper look.

Publication reputability. Large publications will usually have a reputation of fact-checking, but this is not always the case. Some obvious sources to steer away from or check rigorously are gossip sites (based on third-hand information and rumours), promotional sites (which are trying to sell something), and sites with extremist views. Here is one list of websites that you might use to gauge a publication’s fact checking reliability.

Editorials. Although you can use editorials to attribute a stated opinion to its author, take care not to cite what authors say in editorials/opinion pieces as fact without checking.

Age of source. Even when referencing a paper from a reputable, academic, peer-reviewed journal, its age may indicate outdated information. An article’s age may not immediately determine its exclusion, but when in doubt, search more.

Often, these points will be all you need to consider—you may already be using these guidelines when finding sources! If you want more details, I’d suggest scrolling through Wikipedia’s thorough guidelines for reliable sources.

Preserving Digital Data

Digital information disappears all the time for myriad reasons. Sisyphean is the task of saving every byte of digital data, but you may be surprised to learn just how pervasive digital decay is. Even general sources that you might easily consider reputable have plenty of unretrievable digital data; an analysis performed by the Pew Research Center (2024) claims that “23% of news webpages contain at least one broken link, as do 21% of webpages from government sites.”

If you want to cite information on a site that does not exist currently but existed in the past, try to find it on the Wayback Machine or archive it yourself. It’s incomplete in the face of the quadrillions of bytes of human history, but many websites have still been snapshotted at different points of time.

Sometimes you’ll want to quote from a public post on social media to illustrate an author’s opinions. However, the nature of social media is nebulous, and such legitimate primary sources can disappear for any reason. It’s important to personally screenshot or to even snapshot the page on the Wayback Machine so at the very least you have proof to refer to.

This applies outside social media to any online information. Generally, if a source is just a webpage without an obvious date of publication (unlike an article hosted online), it’s worth a look at the Wayback Machine to see if it’s been archived recently.

If you find a source that has not been published or that has been removed, keep a copy! It may not be a completely legitimate or reputable source, but at the very least if you reference it then you have some record of the document.

How to Write a Citation (Finally!)

Now that you’ve found your sources and made sure they’re reliable and archived, you’re ready to sit down and write citations. But do you need to cite everything? How about direct quotes versus paraphrased information?

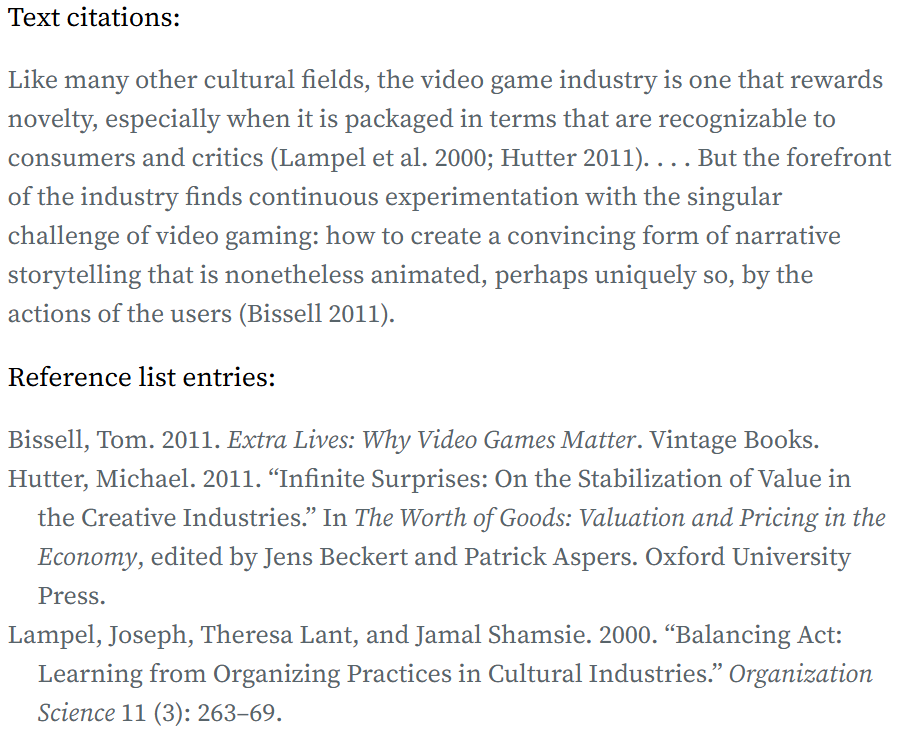

Let’s start with style guides. The CMOS has two main citation styles: the notes and bibliography style or the author-date style. Whichever style you use is up to preference; if the publisher doesn’t require anything specific, then you can go with what’s common for the field you’re writing in. Here’s an overview of use cases from the CMOS Citation Quick Guide:

Notes and Bibliography system:

The notes and bibliography system, Chicago’s oldest and most flexible, can accommodate a wide variety of sources, including unusual ones that don’t fit neatly into the author-date system. For this reason, it is preferred by many working in the humanities, including literature, history, and the arts.

(Note: the year is highlighted to underscore its different placement in this style from the Author-Date style below; the year should not be highlighted in your manuscript.)

Author–Date system:

Because it credits researchers by name directly in the text while at the same time emphasizing the date of each source, the author-date system is preferred by many in the sciences and social sciences.

an excerpt from the Chicago Manual of Style

Integrating Information into Your Text

You have your information, you’ve picked your style guide and system, and you’re typing away. But you might struggle to integrate the information and still have your writing style feel authentic and flow well. Let’s take a quick look at how you might integrate your research into your writing at the line level.

When introducing external information, think about how it’s relevant to your points and why. For any of these methods, the main formula is brief introduction + information + citation.

Direct Quotes

This method quotes the original source verbatim. These quotes should be enclosed in quotation marks with the citation following.

Their study found that “the prevalence [of childfree adults] is even higher (30%) among women of childbearing age who do not have children” (Neal and Neal 2022).

(Source article for this example: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-15728-z#Sec6)

You might also notice the words in square brackets aren’t part of the original source. If including extra information would facilitate understanding of the quote, then you may add a word or two enclosed in square brackets.

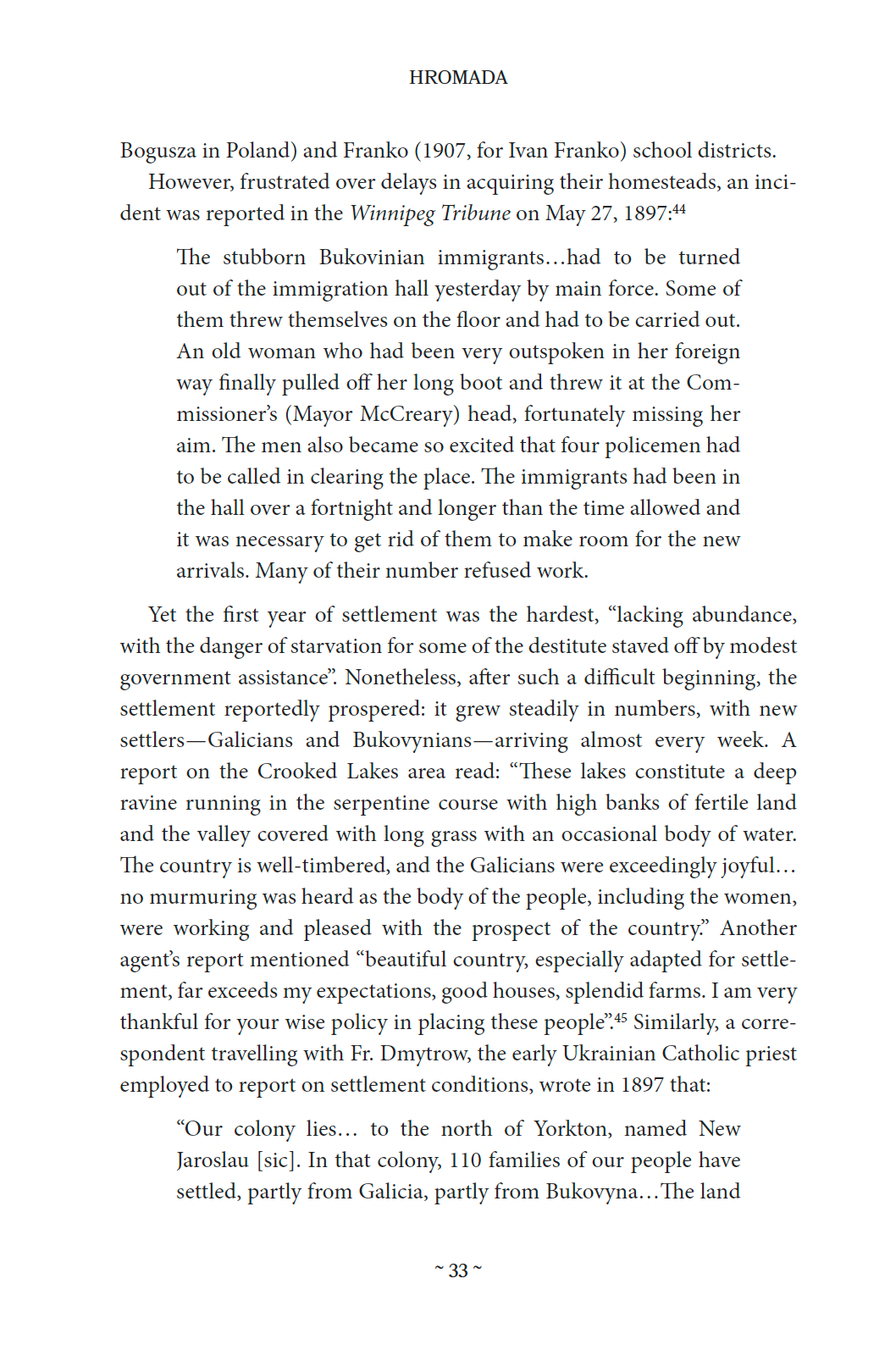

Blockquotes

Blockquotes are a paragraph or more of directly quoted material. These should be used sparingly in favour of using your own original words, as large chunks of text can distract a reader. For example:

Paraphrasing Information

If you reword research that’s not your own original research, you still need to cite. The citation is still an acknowledgement that the information you’re referencing is not yours and can be explored in full at its source.

A multinational study by Egon Dejonckheere et al. (2022) examined the link between a nation’s encouragement of its citizens’ happiness and the actual rate of happiness at macro- and micro-levels.

(Source article for this example: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-04262-z)

Common Pitfalls

Here are some common pitfalls I see authors stumble into when tackling the balance between properly citing information and writing flow:

Claims are too broad

Many experts claim...

It has been scientifically proven...

According to scientific studies...

You may have the information to back up a claim that begins this way, but these are broad claims. If you have specific information, it will always be better to be specific from the get go.

Jane Doe, a tenured professor at Generic University and head researcher at Generic University Labs, claims...

F. Press explores this correlation with studies that...

Experiments performed by A. Researcher et al. support the claims that...

You’ll find that when you’re specific, you end up integrating information about the source in your sentences too.

Misattributing sources

Studies in Psychological Review reveal...

The British Journal of Sociology states...

These too are broad claims, but rather than attributing the information to a certain author or paper, these claims are assigning the sources as an entire scientific journal. Instead:

In this paper published in Psychological Review...

The nth volume, mth issue of the British Journal of Sociology includes a paper about...

Awkward Introductions/Split Quotes

There’s a lot of water on earth! “About 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is water-covered, and the oceans hold about 96.5 percent of all Earth's water” (U. S. Geological Survey 2019).

(Source webpage for this example: https://www.usgs.gov/water-science-school/science/how-much-water-there-earth?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects)

At first glance, this looks like a pretty standard execution of an introduction, quote, and citation. But the quote floats freely from the introduction in a separate sentence. While not strictly incorrect, it feels awkward because you should use quotes to back up your claims rather than having them as self-contained statements.

Bibliography or Reference List?

The end is near! Now all you need to do is compile the sources you’ve used and then put them in a bibliography or references list. There’s nothing complicated about this; the struggle is from whether you’ve kept good track of your information along the way.

For CMOS, you include a bibliography when using the notes system (such as footnotes or endnotes). A bibliography is a list of all the sources you used to write your work regardless of whether you directly cited them. That is, if you used a source to build or inform your arguments when drafting your work, it should be included in the bibliography

When using the author-date system, you include a reference list. Unlike a bibliography, you should only include sources that you directly cited in your work. That is, each citation should have a corresponding entry in the reference list.

Conclusion

Citations seem like a lot of work, but they don’t have to be so consuming that you get distracted from writing or put them off. I hope this article gives you a good starting point for thinking about how citations, source finding, and incorporating them into your writing require different mindsets. The good news is you don’t have to be apprehensive about writing citations—you just need to be organized.

Reference List

Here are the sources used in this article:

Chicago Manual of Style. Accessed 2025. “Chicago-Style Citation Quick Guide.” https://web.archive.org/web/20250728115759/https://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html.

Pew Research Center. May 2024. “When Online Content Disappears.”

https://www.pewresearch.org/data-labs/2024/05/17/when-online-content-disappears/.

Adam Mongaya (he/him) is an editor, a reader, a lover, and a dreamer. He especially loves editing queer romance, but he also has a sharp eye for detail that he hones for fact checking and citation fixing in nonfiction. Before pursuing his certificate in Editing Standards at Queen’s University, he obtained a Social Development Studies degree from the University of Waterloo, where his time as an RA shaped his love for editing written works and helping others express themselves.